The History of Ballymagaleen

Historia Ballymagaleensis

The Age of Saints and Sods (5th–9th Centuries)

According to Giles, Ballymagaleen was first evangelised by Saint Patrick, though the saint’s

memoirists curiously omit this episode—perhaps because he left in haste. Patrick was allegedly

lured there by a druid named Príomhsheans mac Caorach, who converted when he realised that

Christianity offered superior expense accounts. Príomhsheans, having taken holy orders, became

Ireland’s first patron saint of idiots, and is still invoked by poets, politicians, and anyone

attempting to operate a tractor without oil.

A later disciple, Saint Pierian the Hydrated, established a holy well beneath a hazel tree,

promising that its waters would cure ignorance “if drunk deeply enough.” Giles notes that no one

has yet survived the prescribed dose.

The early Ballymagaleen monks were renowned for their illuminated manuscripts, most famously The Book of Slightly Wrong Translations, in which the Beatitudes appear as “Blessed are the cleesemakers, for they shall inherit the mirth.” These monks, however, converted back to paganism after a tax dispute with the local bishop, inventing the unique Irish heresy of Fiscopalianism, which held that salvation was deductible at source.

II. The Era of Raids and Relapses (10th–16th Centuries)

The Vikings raided Ballymagaleen several times but usually left empty-handed, describing it in the Annals of Ulster as “a place without loot but abundant in confusion.” The na Magadhlín sept rose during this period, alternating loyalties between Norsemen, Normans, and whichever side was furthest from paying wages.

By the 14th century, a Carmelite priory dedicated to Saint Simon Stockholder had been founded.

Its monks were famous for producing a liqueur that combined spiritual contemplation with

blindness in roughly equal measure. When Henry VIII’s commissioners arrived to dissolve the

monasteries, they found the priory already dissolved—in poitín.

III. The Age of Confusions (17th–18th Centuries)

The na Magaleens were, by turns, royalists, parliamentarians, Jacobites, Williamites, and smugglers —sometimes all before breakfast. The clan’s fortunes reached their moral zenith and financial nadir when Sir Ulick na Magaleen, 4th Baronet, pledged allegiance to both James II and William III, receiving from each a worthless title and a very fine hangover.

During the Penal era, Ballymagaleen became a haven for recusant priests, unrepentant Protestants,and the hopelessly ecumenical. Giles attributes the village’s dual churches—both dedicated to Saint Príomhsheans—to this theological ambiguity, “one for those escaping Rome and one for those fleeing Canterbury, both praying for the same hangover to end.”

IV. The Age of Famine and Folly (19th Century)

The Great Famine found Ballymagaleen relatively unscathed: its population had already starved

morally. The na Magaleens, always entrepreneurial, exported sympathy to England and imported

gin. A local invention, the Magaleen Method of potato storage (burying them in the landlord’s

orchard at night), remains controversial.

In this century the Fair of Eejits was formalised, a festival at which the most foolish Gael in

Ireland was crowned Ard-Amadán na nGael and rewarded with a hogshead of poitín. “This,” Giles

notes approvingly, “was Ireland’s earliest form of democracy.”

V. The Age of Steam and Scepticism (late 19th–early 20th Centuries)

The railway reached nearby towns but declined to enter Ballymagaleen after an engineer was

offered his own weight in potatoes to reroute it through the Holy Well. The first motorcar to visit, a 1908 Crossley, was mistaken for the Beast of Revelation and shot at by the curate.

The na Magaleen family diversified into politics, poetry, and petty larceny. One ancestor, Lord

Fintan “The Improvident” na Magaleen, introduced an Irish Home Rule Bill entirely written in

Latin, “so as to preserve the purity of its irrelevance.”

VI. The Age of Modernity and Mistakes (20th Century)

The War of Independence passed Ballymagaleen largely unscathed—both sides got lost on the way.

The Free State later classified the village as “strategically unimportant,” which suited everyone.

During the Emergency (known elsewhere as World War II), the na Magaleens operated a thriving

black-market trade in rubber boots, contraceptives, and philosophical pamphlets banned by the

censors.

Electricity came in 1966, though Giles insists the place has never truly been enlightened. Television followed, bringing both soap opera and Manchester United fandom, which he regards as the same plague.

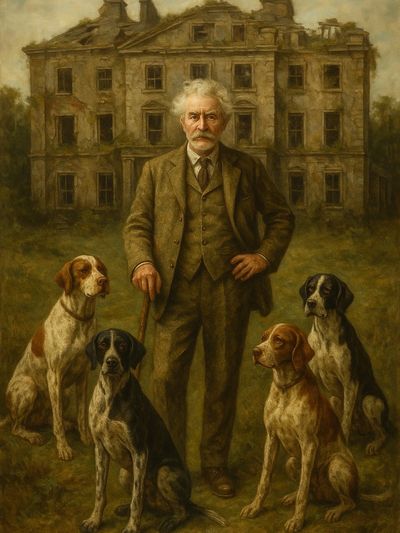

VII. The Age of Giles (late 20th–21st Centuries)

With the death of the old landlord (from laughter, after reading his own overdraft), Giles na

Magaleen inherited Cashelmagaleen House and promptly declared it a Free Intellectual Republic.

He maintains feudal rights over all confusion within parish boundaries and collects his rent in

gossip, good whiskey, and occasional pheasants.

Ballymagaleen today, under his informal lordship, remains a peninsula of paradox:

• Two churches with one congregation;

• Three pubs and not a sober publican;

• A school run by an ex-nun who preaches atheism;

• And a Garda sergeant who connives at peace by ignoring all offences until closing time.

Epilogue: “On the Future of Ballymagaleen”

As Giles himself writes in The Annals of Absurdity (a privately circulated manuscript, self-indexed

and self-denied):

“Ireland was not conquered by England, nor freed by Ireland, but mislaid by both and

rediscovered every Saturday night in Ballymagaleen, over the counter at Dooley’s.

Here history is not written—it is merely rehearsed for the next generation of fools.”

FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

(or, Infrequently Answered Questions, depending on mood)

Who exactly is Lord Giles na Magaleen?

An Irish aristocrat of uncertain fortune and impeccable diction. Educated beyond his means and beneath his talents, Giles is the Ninth Earl of Clangiles (by courtesy), hereditary philosopher, and the last man in Connacht to use the subjunctive correctly after whiskey.

Where is Ballymagaleen?

Ballymagaleen is located on a peninsula between fact and fiction, somewhere west of Galway and east of sense. It is reachable by road, myth, or determined imagination. Those relying on GPS are encouraged to bring sandwiches.

Is Cashelmagaleen House open to the public?

Yes, provided the public knocks, curtsies, and brings their own drink. Guided tours are available whenever Lord Giles is sober enough to lead them — a window of opportunity smaller than the average confession box.

What is there to do in Ballymagaleen?

Plenty: drink at Dooley’s, repent at St Pierian’s Holy Well, or argue with a priest of your choice. You may also trace your genealogy, lose your way in the peat hills, or listen to the seals judging humanity from the southern coves.

Who is Sergeant Gombeeni?

The local constable, philosopher, and part-time poet. He ensures that Ballymagaleen remains both law-abiding and delightfully ungovernable. Reports suggest he enforces the peace mainly by ignoring disturbances until they resolve themselves.

Does Ballymagaleen really have two churches with the same name?

Indeed. Both are dedicated to St Príomhsheans, patron saint of fools, poets, and bureaucrats. The Catholic and Church of Ireland congregations maintain separate liturgies but share the same collection plate in a spirit of mutual exasperation.

Are the stories on this website true?

All of them, approximately. Some are more true than others, depending on barometric pressure, audience gullibility, and the day’s exchange rate of nonsense to sincerity.

Can I stay in Ballymagaleen?

Yes, but not indefinitely. The village has limited accommodation and infinite hospitality. Bed, breakfast, and bewilderment are available by arrangement through Miss Shebeena Dooley, usually in exchange for poetry, cash, or gossip.

How can I contact Lord Giles?

By email at service@ballymagaleen.com, by post via Cashelmagaleen House, or by séance if the Wi-Fi is down. Replies are dispatched as soon as Giles has consulted the appropriate oracle (or accountant).

What does “Ridendo Regimus Insaniam” mean?

It is the family motto of the na Magaleens: Through laughter, we govern madness. It also serves as a guiding principle, a legal disclaimer, and the only known cure for contemporary life.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.